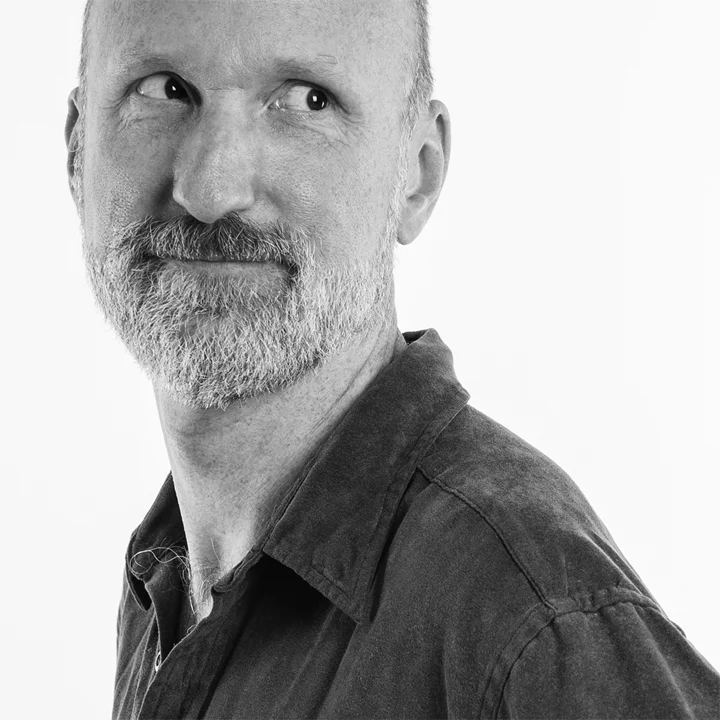

Raymond Luczak

Counterpoint

after Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827)

You appeared fully formed, the locks of your hair

sprouting like a lion’s mane. You were the ghost of music

that followed me all my life: “Isn’t it so amazing

that Beethoven could compose and not hear a thing?”

No one knew I couldn’t hear until I was two years old.

I didn’t understand why someone had to twist my chin

just to look at someone moving their lips at me.

It was all so strange and disturbing.

The ringing in your ears turned into a flooding river.

Catfish scurried between you and the blue sky.

The oxygen tank of notes all in its combinations

from sheer memory kept you breathing underwater.

The first time I truly heard music: horses galloped past

the din of cigarettes and chatter from the gates

exploding beneath the glass dome of the jukebox.

The Bee Gees had arrived in white pantsuits and gold chains.

That noise stopping for a minute: you noticed a missed

note, a certain pitch, an absence. So gradual,

yet when you listened, a ghost of nothingness

whispered screams in your ears. You wanted suicide.

I heard “A Fifth of Beethoven” blasting on the radio.

No words: horns and strings competed relentlessly,

sweltering with the disco beat. Dreams of music were infected

with the malaria of obsession. I had no mosquito netting.

When you could no longer follow a spoken conversation,

you wrote back and forth in one blank book after another.

You didn’t hide much back then. When you died,

your “biographer” destroyed 264 out of those 400 books.

Even back then people wanted to make you a saint.

Disco has become a symphony of nostalgia.

Each year I tear away each scribbled sheet of fear.

Silence too has become my coda.